Space-filling curves, constructively

- 30 January 2024

- Constructive math, Gems and stones

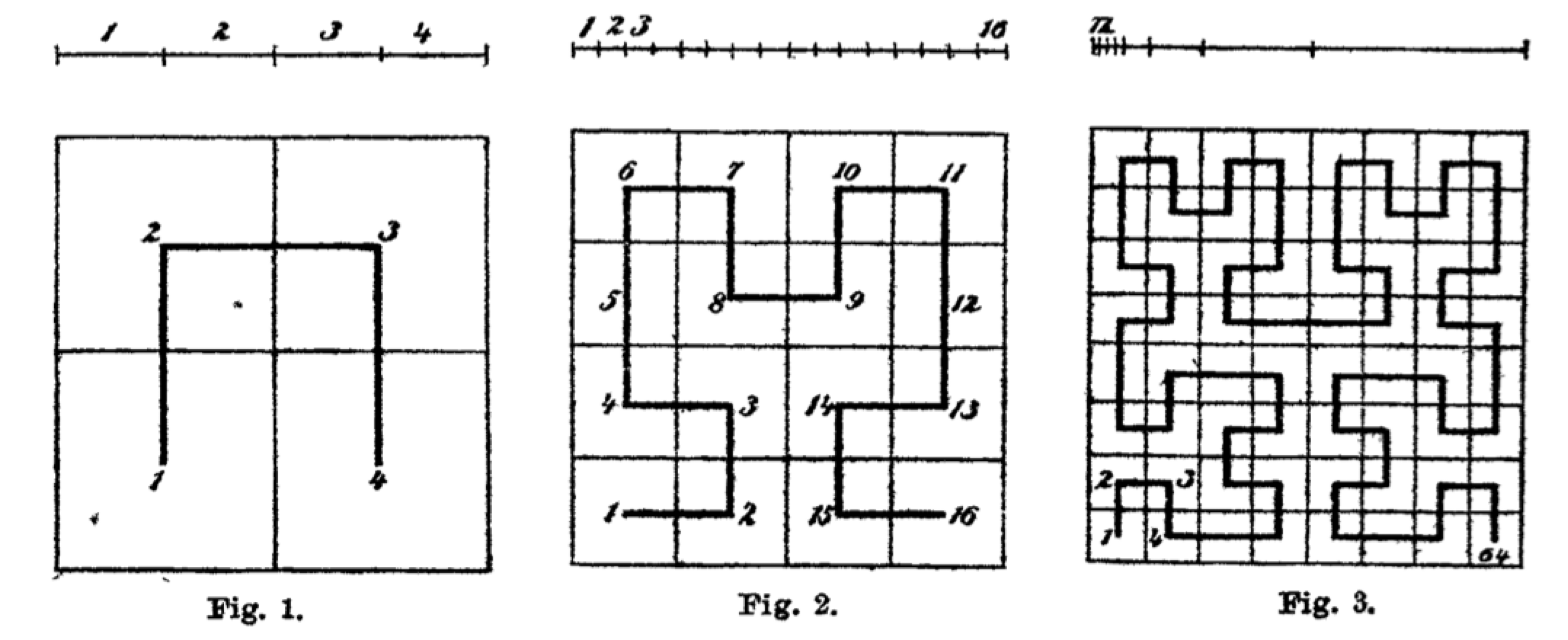

In 1890 Giuseppe Peano discovered a square-filling curve, and a year later David Hilbert published his variation. In those days people did not waste readers' attention with dribble – Peano explained it all on 3 pages, and Hilbert on just 2 pages, with a picture!

But are these constructive square-filling curves?

There's no doubt that the curves themselves are defined constructively, for instance as limits of uniformly continuous maps. A while ago I even made a video showing the limiting process for Hilbert curve:

Is Hilbert's curve constructively surjective? Almost:

Theorem 1: For any point in the square, its distance to Hilbert curve is zero.

Proof. Recall that the Hilbert curve $\gamma : [0,1] \to [0,1]^2$ is the limit of a sequence $\gamma_n : [0,1] \to [0,1]^n$ of uniformly continuous maps, with respect to the supremum norm on the space of continuous maps $\mathcal{C}([0,1], [0,1]^2)$. The finite stages $\gamma_n$ get progressively closer to every point in the square. Thus, for any $\epsilon > 0$ and $p \in [0,1]^2$ there is $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and $t \in [0,1]$ such that $d(p, \gamma_n(t)) < \epsilon/2$ and $d(\gamma_n(t), \gamma(t)) < \epsilon/2$, together ensuring that $\gamma$ is closer than $\epsilon$ from $p$. $\Box$

Classically, Theorem 1 suffices to conclude that Hilbert curve is surjective. Constructively, we have to modify it a bit. Recall that $\gamma$ is self-similar, as it is made of four copies of itself, each scaled by a factor $1/2$, translated and rotated to cover precisely one quarter of the unit square. Therein lies the problem: the four abutting quarter-sized squares cannot be shown to cover the unit square. We should make them slightly larger so that they overlap.

Given a scaling factor $\alpha$, let us define the generalized Hilbert curve $\gamma^\alpha : [0,1] \to [0,1]^2$ constructed just like the usual Hilbert curve, but with scaling factor $\alpha$. Instead of writing down formulas in LaTeX, it is more fun to program the curve in Mathematica and draw some pictures (see IntuitionisticHilbert.nb).

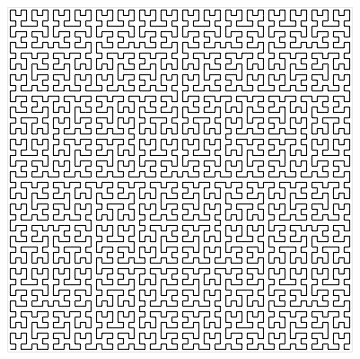

At $\alpha = 0.5$ we recover the usual Hilbert curve:

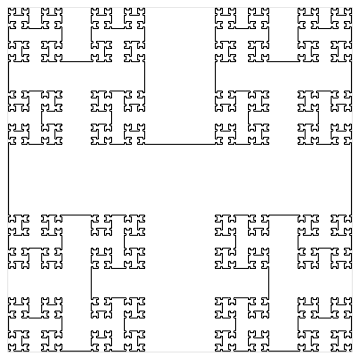

At $\alpha = 0.4$ the curve is not square-filling:

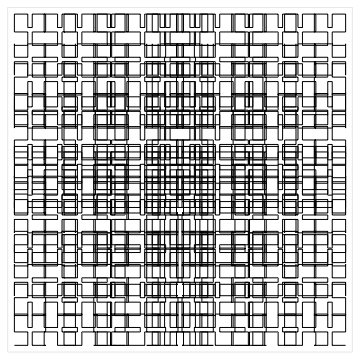

At $\alpha = 0.6$ we obtain a square-filling curve that overlaps itself already at finite stages:

This is the one we want.

This is the one we want.

Just for fun, here's a video the 8-th level curve as $\alpha$ ranges from $0.4$ to $0.8$.

As $\alpha$ increases the image gets denser in the center of the square and sparser close to the boundary, but this is an artifact of showing a finite stage. The actual curve $\gamma^\alpha$ is equally dense everywhere as soon as $\alpha > 0.5$. Back to serious business:

Theorem 2: Assuming dependent choice, the generalized Hilbert cube $\gamma^\alpha$ is surjective for $1/2 < \alpha < 1$.

Proof. Define the transformations $T_0^\alpha, T_1^\alpha, T_2^\alpha, T_3^\alpha : [0,1]^2 \to [0,1]^2$:

- $T_0^\alpha(x,y) = (\alpha \cdot y, \alpha \cdot x)$

- $T_1^\alpha(x,y) = (\alpha \cdot x, 1 - \alpha \cdot (y - 1))$

- $T_2^\alpha(x,y) = (1 - \alpha \cdot (x - 1) , 1 - \alpha \cdot (y - 1))$

- $T_3^\alpha(x,y) = (1 - \alpha \cdot y , \alpha \cdot (1 - x))$

Each of these map the unit square onto a smaller square with side $\alpha$:

- $T_0$ scales and reflects the unit square onto $[0,\alpha] \times [0,\alpha]$

- $T_1$ scales the unit square onto $[0,\alpha] \times [1 - \alpha, 1]$,

- $T_2$ scales the unit square onto $[1 - \alpha, 1] \times [1 - \alpha, 1]$,

- $T_3$ scales and reflects onto $[1 - \alpha, 1] \times [0, \alpha]$.

Because $\alpha > 1/2$ these four squares overlap (rather than just touch) therefore they cover $[0,1]^2$, constructively. Given any $p \in [0,1]^2$ we may use Dependent choice to find a sequence of $T_{i_1}, T_{i_2}, T_{i_3}, \ldots$ such that $p = T_{i_1} (T_{i_2} (T_{i_3} (\cdots)))$, hence $p = \gamma^\alpha(t)$ where $t \in [0,1]$ is the number $0.i_1 i_2 i_3 \ldots$ written in base 4. $\Box$

Can we also do it without Dependent choice? We certainly cannot get rid of all choice.

Theorem 3: In the topos of sheaves on the unit square $\mathrm{Sh}([0,1]^2)$ there is no square-filling curve.

Proof. Let $I$ be the unit interval in the topos, i.e., it is the sheaf of continuous maps valued in $[0,1]$. Consider the internal statement that there is a surjection from $I$ onto $I^2$:

$$\exists \gamma : I \to I^2 .\, \forall p \in I^2 .\, \exists t \in I .\, \gamma(t) = p \tag{1}$$

Working through sheaf semantics (thanks to Andrew Swan for doing it with me over a cup of coffee – although I claim ownership of all errors), its validity at an open set $U \subseteq [0,1]^2$ amounts to the following condition: there is an open cover $(U_i)_i$ of $U$ with continuous maps $\gamma_i : U_i \times [0,1] \to [0,1]^2$ such that, for every $i$, every open $V \subseteq U_i$ and continuous $p : V \to [0,1]^2$, there is an open cover $(V_j)_j$ of $V$ and continuous maps $t_j : V_j \to [0,1]$, such that $\gamma_i(v, t_j(v)) = p(v)$ for all $j$ and $v \in V_j$.

Instantiate $p : V \to [0,1]^2$ in the stated condition with the inclusion $p(v) = v$ to obtain, for every $j$, that $\gamma_i(v, t_j(v)) = v$ holds for all $v \in V_j$. Therefore, the map $\gamma_i{\restriction}_{V_j} : V_j \times [0,1] \to V_j$ has a continuous section, namely the map $v \mapsto (v, t_j(v))$. But there can be no such map, as it would violate invariance of domain, unless $V_j = \emptyset$. Consequently, the only way for (1) to hold at $U$ is for $U$ to be empty. $\Box$

To summarize the argument: in a topos of sheaves “$\gamma$ is surjective” is a very strong condition, namely that $\gamma$ has local sections – and these may not exist for topological or geometric reasons. At the same time we still have Theorem 1, so also in a topos of sheaves the usual Hilbert curve leaves no empty space in the unit square.

andrejbauer@mathstodon.xyz, I will

gladly respond.

You are also welcome to contact me directly.